Saffron (pronounced /ˈsæfrən/ or /ˈsæfrɒn/) is a spice derived from the flower of Crocus sativus, commonly known as the saffron crocus. Crocus is a genus in the family Iridaceae. Each crocus grows to 20–30 cm (8–12 in) and bears up to four flowers, each with three vivid crimson stigmas, which are each, the distal end of a carpel. Together with the styles, or stalks that connect the stigmas to their host plant, the dried stigmas are used mainly in various cuisines as a seasoning and coloring agent. Saffron, long among the world’s most costly spices by weight, is native to Greece and was first cultivated there. It was slowly propagated throughout much of Eurasia and was later brought to parts of North Africa, North America, and Oceania.

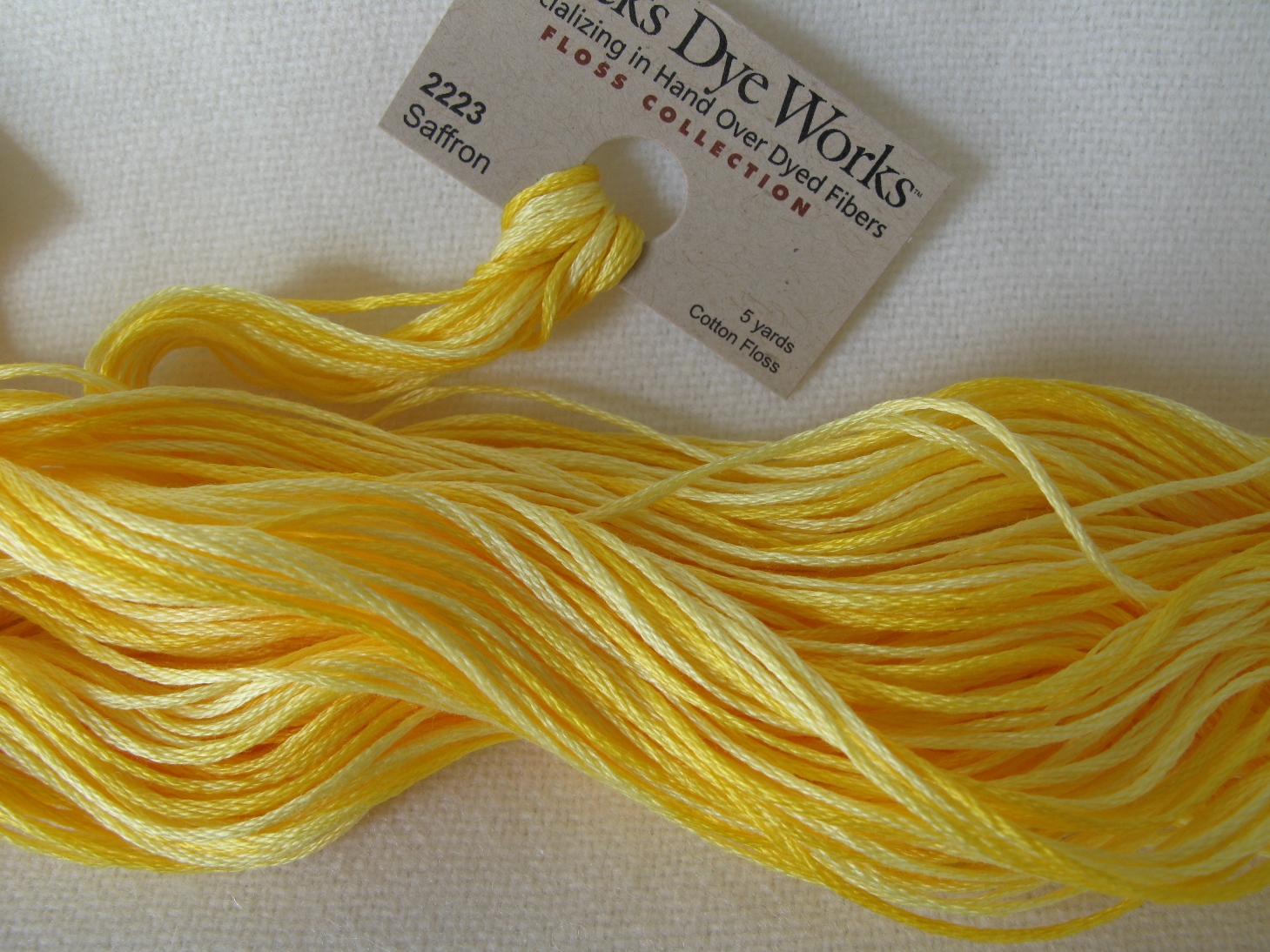

Saffron’s bitter taste and iodoform- or hay-like fragrance result from the chemicals picrocrocin and safranal. It also contains a carotenoid dye, crocin, which imparts a rich golden-yellow hue to dishes and textiles. Its recorded history is attested in a 7th-century BC Assyrian botanical treatise compiled under Ashurbanipal, and it has been traded and used for over four millennia. Iran now accounts for approximately 90 percent of the world production of saffron.

Saffron features in European, North African, and Asian cuisines. Its aroma is described by taste experts as resembling that of honey, with grassy, hay-like, and metallic notes. According to another such assessment, it tastes of hay, but only with bitter hints. Because it imparts a luminous yellow-orange hue, it is used worldwide in everything from cheeses, confectioneries, and liquors to baked goods, curries, meat dishes, and soups. In past eras, many dishes called for prohibitively copious amounts—hardly for taste, but to parade their wealth.

Because of its high cost saffron was often replaced by or diluted with safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) or turmeric (Curcuma longa) in cuisine. Both mimic saffron’s color well, but have distinctive flavors. Saffron is used in the confectionery and liquor industries; this is its most common use in Italy. Chartreuse, izarra, and strega are types of alcoholic beverages that rely on saffron to provide color and flavor. The savvy often crumble and pre-soak saffron threads for several minutes prior to adding them to their dishes. They may toss threads into water or sherry and leave them to soak for approximately ten minutes. This process extracts the threads’ color and flavor into the liquid phase; powdered saffron does not require this step. The soaking solution is then added to the hot cooking dish, allowing even color and flavor distribution, which is critical in preparing baked goods or thick sauces.

Threads are a popular condiment for rice in Spain and Iran, India and Pakistan, and other countries. Two examples of such saffron rice are the zarzuela fish-seafood stew and paella valenciana, a piquant rice-meat preparation. It is essential in making the French bouillabaisse, which is a spicy fish stew from Marseilles, and the Italian risotto alla milanese. The saffron bun has Swedish and Cornish variants and in Swedish is known as lussekatt (literally “Lucy cat”, after Saint Lucy) or lussebulle. The latter is a rich yeast dough bun that is enhanced with saffron, along with cinnamon or nutmeg and currants. They are typically eaten during Advent, and especially on Saint Lucy’s Day. In England, the saffron “revel buns” was traditionally baked for anniversary feasts (revels) or for church dedications. In the West of Cornwall, large saffron “tea treat buns” signifies Methodist Sunday School outings and activities.

Moroccans use saffron in their tajine-prepared dishes, including kefta (meatballs with tomato), mqualli (a citron-chicken dish), and mrouzia (succulent lamb dressed with plums and almonds). Saffron is the key ingredient in the chermoula herb mixture that flavors many Moroccan dishes. Uzbeks use it in a special rice-based offering known as “wedding plov” (cf. pilaf). Saffron is also essential in chelow kabab, the Iranian national dish. South Asian cuisines use saffron in biryanis, which are spicy rice-vegetable dishes. (An example is the Pakki variety of Hyderabadi biryani.) Saffron spices subcontinental beef and chicken entrees and goes into many sweets, particularly in Muslim and Rajasthani fare. Modern technology has added another delicacy to the list: saffron ice cream. Regional milk-based sweets feature it, among them gulab jamun, kulfi, double ka meetha, and “saffron lassi”; the last is a sweet yogurt-based Jodhpuri drink that is culturally symbolic.

Saffron’s folkloric uses as an herbal medicine are legendary and legion. It was used for its carminative (suppressing cramps and flatulence) and emmenagogic (enhancing pelvic blood flow) properties. Medieval Europeans used it to treat respiratory disorders—coughs and colds, scarlet fever, smallpox, cancer, hypoxia, and asthma. Other targets were: blood disorders, insomnia, paralysis, heart diseases, stomach upsets, gout, chronic uterine hemorrhage, dysmorrhea, amenorrhea, infant colic, and eye disorders. For the ancient Persians and Egyptians saffron was an aphrodisiac, a general-use antidote against poisoning, a digestive stimulant, and a tonic for dysentery and measles. European practitioners of the archaic and quixotic “Doctrine of Signatures” took its yellowish hue as a sign of its putative curative properties against jaundice.

Initial research suggests that carotenoids present are anticarcinogenic (cancer-suppressing), anti-mutagenic (mutation-preventing), and immunomodulatory. Dimethylcrocetin, the compound thought responsible for these effects, counters a wide range of murine (rodent) tumors and human leukemia cell lines. Saffron extract also delays ascites tumor growth, delays papilloma carcinogenesis, inhibits squamous cell carcinoma, and decreases soft tissue sarcoma incidence in treated mice. Researchers theorize that, based on the results of thymidine-uptake studies, such anticancer activity is best attributed to dimethylcrocetin’s disruption of the DNA-binding ability of a class of enzymes known as type II topoisomerases. As topoisomerases play a key role in managing DNA topology, the malignant cells are less successful in synthesizing or replicating their own DNA.

Saffron’s pharmacological effects on malignant tumors have been documented in several studies: it extends the lives of mice that are intraperitoneally impregnated with transplanted sarcomas, namely, samples of S-180, Dalton’s lymphoma ascites (DLA), and Ehrlich ascites carcinoma (EAC) tumors. Researchers followed this by orally administering 200 mg (0.0071 oz) of saffron extract for each kg of mouse body weight. As a result the life spans of the tumor-bearing mice were respectively altered to 111.0%, 83.5%, and 112.5% of the baseline or reference span. Researchers also discovered that saffron extract exhibits cytotoxicity in relation to DLA, EAC, P38B, and S-180 tumor cell lines cultured in vitro. Thus, saffron has shown promise as a new and alternative treatment for a variety of cancers.

Besides wound-healing and anticancer properties, saffron is also an antioxidant. This means that, as an “anti-aging” agent, it neutralizes free radicals. Methanol extractions of saffron neutralize at high rates the DPPH (IUPAC nomenclature: 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) radicals. This occurred via vigorous proton donation to DPPH by two of saffron’s active agents, safranal and crocin. At concentrations of 500 and 1000 ppm, crocin studies showed neutralization of 50% and 65% of radicals, respectively. Safranal displayed a lesser rate of radical neutralization than crocin. Such findings give saffron extracts promise as an ingredient for use as an antioxidant in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and as a food supplement. Antidepressant effects have been demonstrated.

Despite its high cost, saffron has been used as a fabric dye, particularly in China and India. It is in the long run an unstable coloring agent; the imparted vibrant orange-yellow hue quickly fades to a pale and creamy yellow. Even in minute amounts, the saffron stamens yield a luminous yellow-orange; increasing the applied saffron concentration will give fabric of increasingly rich shades of red. Clothing dyed with saffron was traditionally reserved for the noble classes, implying that saffron played a ritualized and status-keying role.

It was originally responsible for the vermilion-, ochre-, and saffron-hued robes and mantles worn by Buddhist and Hindu monks. In medieval Ireland and Scotland, well-to-do monks wore a long linen undershirt known as a léine, which was traditionally dyed with saffron. In histology the hematoxylin-phloxine-saffron (HPS) stain and Movat’s pentachrome stain are used as a tissue stain to make biological structures more visible under a microscope. Saffron stains collagen yellow.

There have been many attempts to replace saffron with a cheaper dye. Saffron’s usual substitutes in food—turmeric and safflower, among others—yield a garishly bright yellow that could hardly be confused with that of saffron. Saffron’s main colorant is the flavonoid crocin; it has been discovered in the less tediously harvested—and hence less costly—gardenia fruit. Research in China is ongoing.[35] In Europe saffron threads were a key component of an aromatic oil known as crocinum, which comprised such motley ingredients as alkanet, dragon’s blood (for color), and wine (again for color). Crocinum was applied as a perfume to hair. Another preparation involved mixing it with wine to produce a viscous yellow spray; it was copiously applied in sudoriferously sunny Roman amphitheatres—as an air freshener.